'Nowhere Else to Go': How northern Michigan's senior housing shortage is exacerbating every other market hurdle

October 2025

“It’s really bad.”

That’s Yarrow Brown’s quick and blunt status report on the senior housing situation in northern Michigan. Despite the Grand Traverse area’s status as a desirable retirement destination, the numbers show that the region is woefully unprepared to house its ever-growing population of senior citizens – at least without some major changes to local zoning and development trends.

Brown

BrownAs executive director for Housing North, Brown is no stranger to the often-dire facts and figures that characterize northern Michigan’s housing problem. A nonprofit organization formed in 2018, Housing North works to “build awareness, influence policy and grow capacity and resources for housing solutions” across the 10-county region of Antrim, Benzie, Charlevoix, Emmet, Grand Traverse, Kalkaska, Leelanau, Manistee, Missaukee and Wexford counties.

Every few years, Housing North embarks upon a data-rich deep dive to prepare a housing needs assessment covering all 10 counties. The most recent of those reports, published in 2023, looked at existing and projected housing gaps across the 10 counties from 2022 and 2027, estimating that northern Michigan would be more than 30,000 residential units short of its housing needs by 2027, including 8,813 rental units and 22,455 for-sale units.

Those numbers, Brown acknowledges, are severe enough to guarantee that virtually every local resident is affected in some way by the housing shortage, whether in the form of skyrocketing housing costs or staffing challenges at local businesses. For seniors, though, Brown says the problem is even more complicated because of how it compounds with other factors, like the need to live on a fixed income or the desire to find a home that is conducive to aging in place.

Susan Leithauser-Yee, a real estate industry professional and a technical support coordinator for Housing North’s Housing Ready program, says a big part of the challenge around senior housing in the region is the broad and amorphous definition for what “senior housing” actually looks like.

“When we are talking about senior housing, seniors could be in their own homes; they could be in a downsized home they moved into after retiring; they could be living with a loved one; or they could be in a senior community, where there’s this whole spectrum of independent, assisted, skilled nursing or primary care facilities,” Leithauser-Yee explained. “There are just a lot of different segments within senior housing, and that makes it hard to track where the need is.”

Hard to track or not, the need is there. In a stakeholder survey done as part of the 2023 Housing Needs Assessment, senior-specific housing – including independent living, assisted living and nursing care communities – was consistently rated as a moderate to high need, particularly for groups with lower incomes of $25,000 or less. Brown expects those needs will only grow as some of the cheapest real estate inventory in the region increases in price, thereby displacing the people – including fixed-income seniors – that call those places home.

“Susan's been sitting on a Grand Traverse County workgroup looking specifically [at housing displacement],” Brown said. “It came up a lot during the election, when people were canvassing. One of the state reps was hearing from a lot of people being displaced, especially in the manufactured home communities around here. We are especially seeing a lot of people on fixed incomes being displaced more rapidly, and that’s mostly people who are 55 and older.”

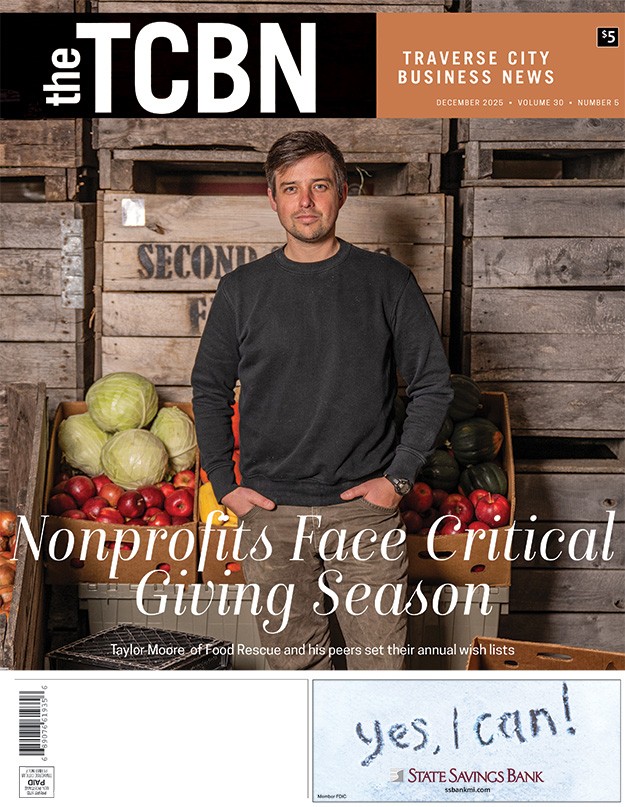

Meadow Valley Senior Living

Meadow Valley Senior LivingA few new senior living communities have come online in the past year or so that could help matters. One example is Meadow Valley Senior Living in Garfield Township, which brought 174 units to the table in independent, assisted and memory-care categories when it opened in 2024. But the region has also lost some facilities in recent years, leading to a “two steps forward, one step back” type situation. In 2021 for example, Northern Star Assisted Living, a 65-bed facility on Munson Avenue, shut down for good, citing staffing problems. After years of sitting vacant, the building finally reopened in a renovated form this year, now as a hotel called The Vic.

One of the biggest problems, according to Leithauser-Yee, is that aging adults rely on a continuum of options for housing and care. In a perfect system, people would be able to age to a certain point in their long-term homes, downsize to smaller, more accessible dwellings to age in place and lean on in-home care as needed, and then move to senior living communities or nursing facilities as health and ability demand. Without enough capacity or affordability in all or most of those categories, though, the continuum breaks apart, which then causes a domino effect that impacts the entire housing market.

“There are a lot of seniors in our area right now who live in these larger homes, but they don't really have anywhere to go to downsize into a lower-cost situation,” Leithauser-Yee explained.

Brown adds that this immobility causes additional complexities.

“And then when people aren’t leaving their homes because there's nowhere else to go, not only does that impact the senior looking to downsize, but it also means that you have all these four-bedroom houses that are locked up with one or two-person households,” she said.

All told, the Housing Needs Assessment found that nearly 57% of households in the 10-county region have heads-of-household who are 55 years old or older. Moreover, virtually all of the projected household growth in the region by 2027 is expected to come in the form of older households, including 3,758 additional 75-plus households and 2,114 more 65-74 households. For comparison’s sake, in the same time frame, the region is expected to see a net loss of 1,157 households aged 25-34, and a gain of just 841 households in the 35-44 demographic.

The solution, Brown and Leithauser-Yee say, will involve a lot of different components. More senior living communities setting up shop in the area would help, particularly if they were focused on providing space and services at a more affordable price point. (“I don’t want to pick on local providers, but at one of the newer senior living communities in town, a one-bedroom is $5,200 a month," Leithauser-Yee noted.) More housing developers focusing on designing and building age-in-place-ready homes would help, too.

“We're noticing that, with Habitat for Humanity, they're building their homes completely ADA-accessible now, which is a great trend,” Brown said.

Leithauser-Yee

Leithauser-YeeMore than likely, though, younger people will have to get involved and be proactive to ensure that their parents and grandparents have living options. Depending on income level, that might mean getting on a waiting list for a Traverse City Housing Commission unit – waiting lists that Brown says “are years long” – or normalizing roommate arrangements for older adults.

“We’re definitely looking at how we can teach people how to be roommates again, and at giving them best practices to follow for sharing a kitchen space or other living spaces,” Brown said.

Leithauser-Yee, for her part, is also a strong proponent of popularizing accessory dwelling units (ADUs) as a senior housing option. ADUs have been a bit of a political football in northern Michigan over the years, with some locals worrying about them being used as short-term rentals or simply adding too much density to local neighborhoods. When it comes to older loved ones looking to downsize into smaller, more manageable, and more affordable living situations, though, Leithauser-Yee argues that families could solve a lot of problems by going down the ADU path.

“If we had an ADU added to every block in the city, that would solve part of the problem,” Leithauser-Yee said. “Now, if you build a free-standing backyard apartment, which is the concept we often think about with ADUs, that’s probably going to be cost-prohibitive for a lot of people, both in terms of construction costs and because of the big bump in taxes from adding square footage. But we’ve started trying to educate people on a lower-cost solution, where maybe you can convert existing square footage in your home to house a family member, and if you want some privacy, maybe add a bathroom and a second entrance.”

Brown says that kind of thinking is "definitely" needed now.

“We need to encourage these different types of living spaces and get people comfortable with the resources of how you would create that kind of space,” she said.

More than anything else, though, Brown thinks locals need to let go of their “resistance to zoning changes,” whether that's rules that bar or limit ADUs or even the city’s closely guarded building height limitations.

“We can't keep putting up barriers to housing,” she said flatly.